1840s-1850s JAGAR George with Mr MANISTY

1858-72 JAGER George & Co

1840s-1850s JAGAR George with Mr MANISTY

1858-72 JAGER George & Co

1867-1925 JAGER George & Co (no.77)

1869-1921 TATE Henry & Sons (no.12)

1921-1981 TATE & LYLE

1832 VICCARS John

1847-53 JAGER George (no.6&2A)

1852?-1872 LEITCH James & Co (no.14)

1853 VICKERS & Son (no.6)

1853?-1872 CROSSFIELD Edward & Co (no.20)

1852-1872 LEITCH James & Co (no.19 Well' St, nos.13-17 Ell' St)

1860-2 TATE Henry & Sons

1824-5 MORGENSTERN & MOLLENHAUER (no.14)

1827-9 THORNHILL William (no.16)

1827-9 TORICK Henry John (Barton's Lane)

1827-9 WEBB & MEHRTENS (no.17)

1853 LEITCH James (no.15)

1816-7 ERCKS Henry (no.52)

1824-5 MORGENSTERN & MOLLENHAUER (no.57)

1816-7 DISTEL & Co

1832 SUMMERFIELD William P

1835 RING

1847-1866 FAIRRIE JT & A (no.213)

1853-1872 CROSSFIELD, BARROW & Co (no.32)

1863 LIGHTFOOT Thomas

1866-1929 FAIRRIE & Co Ltd (no.253)

1899 CRIDDLE William E (no.245)

1841 MACFIE

1846-1872 MACFIE & Sons

1847 WALKER, WRIGHT & Co (no.16)

1864 SCHULTZ Henry

1827-9 MORGENSTERN Henry & Son (no.30)

1835 OWENS Richard (no.31)

1843 MOLLENAUR Henry (left for Utah 1852)

1805-7 CARSON, ATHERTON & DISTELL

1835-47 RING & VICKERS (no.3)

1853 RING & Son (nos.2-3)

1899 FREEMAN, LLOYD & Co

LIVERPOOLCLICK the (For local directory of sugar houses, click here.) (For national directory of sugar houses, click here.) |

|

|

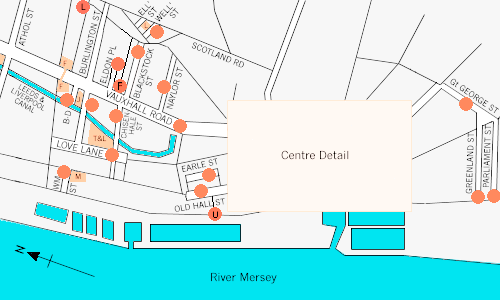

The length of this map represents 2.2ml / 3.5km. |

|

Contents ... |

|

Background. "About the year 1544 refining of sugar was first used in England. There were but 2 sugar-houses; and the profit was little, by reason there were so many sugarbakers in Antwerp and thence better and cheaper than it could be afforded in London."Sugar cane, from which the raw sugar was extracted in the 13th century by the Venetians, came from Egypt where it had been grown for thousands of years. But it was slavery and the 'triangle trade' which created a boon in sugar refining. The Portuguese, French & Dutch were into the business sometime before the British. In Britain, Bristol and London ships were first to take up the slave trade in the mid 17th-century. Liverpool's first slave ship sailed in 1709, and by 1720 outstripped its rivals. Liverpool's prosperity was built on sugar, tobacco and cotton. Beginnings in Liverpool. Progress in the 18th century.

1. 'Sugar House Yard' - north of the Old Dock and east of Old Strand Street

- this is obviously the site of the presumed first sugar house although by 1769 a long way from

the water's edge with Salt House Dock built in front of it. By 1900 it had been redeveloped. Sugar firms in mid-Victorian Liverpool. Gore's Directory for 1872 (and Watson's book of 1982) lists the following sugar refiners:

In Gore's Directory of 1899 the following names had

appeared as sugar refiners: (probably dealers) Henry Tate & Consolidation in the 20th century. Growth of the Sugar Industry. The Early Processes of Sugar Refining. The German connection. Family connections with sugar. Summary. ........Neville H King: Feb 1997; Revised Oct 2000.

|

|

The earliest reference to the Lancashire sugar industry is in the Moore Rental of 1667-8. In this document Sir Edward Moore, referring to a plot of land in Dale Street, Liverpool, writes as follows:- Sugar-House Close ... This croft fronts the street for some twenty-seven yards and I call it the Sugar House Close, because one Mr Smith, a great sugar-baker at London, a man as report says, worth forty thousand pounds, came from London to treat with me. According to agreement he is to build all the front twenty-seven yards a stately house of good hewn stone ... and there on the back side, to erect a house for boiling and drying sugar, otherwise called a sugar-baker's house ... If this be once done, it will bring a trade of at least forty thousand pounds a year from the Barbadoes, which formerly this town never knew. (1) Whether a sugar-house really was erected in Liverpool during the last quarter of the seventeenth century we have been unable to discover. Indications of a Liverpool sugar industry contained in the Index to Wills of Chester point to a somewhat later date. (2) 1754 Robert Lever, of Liverpool, sugar boiler. Two of these entries, it will be seen, refer to sugar works at Warrington. The earliest mention of sugar at Warrington is in 1755, when Chamberlayne writes, "Warrington is much noted for a large smelting-house for copper as also a sugar-house". (3) Another seat of the sugar industry in Lancashire during the eighteenth century, of which the Index of Wills tells us nothing, was at Manchester. From the Manchester and Salford Directory of 1773 we learn that Sam Norcot, of Water Street, was a sugar baker, and further that Thomas Rothwell was clerk at the Sugar House, Water Street. During the nineteenth century Liverpool has been the chief centre of the sugar refining industry in Lancashire.

|

|

Bundle of documents referring to Share Ownership, etc, of limited company. * 15 May 1866 - Fairrie & Company, Limited - Articles of Association.

* 1866 - Registered Office - Colonial Buildings, 36 Dale St, Liverpool. * Various share allocation certificates through the years, but in 1877 Macfies became majority shareholders. * 1892 Share allocation .....

* 1904 - Registered Office - Palace Chambers, 21 Victoria St, Liverpool. James Fairrie, MD. * 31 May 1924. Articles of Association re-draughted. Excellent document showing 24 "Objects for which the Company is Formed". * 1927 - There were far more shareholders. * Mortgage register shows premises at : Vauxhall Rd, Raymond St, Hornby St, Victoria St, Black Diamond St, land adjacent to Leeds & Liverpool Canal, Green St, Portland St, Burlington St (warehouses & stables). * 2 Aug 1929 - Extraordinary Meeting - resolution duly passed "That Fairrie & Co Ltd be wound up voluntarily and that a liquidator be appointed for the purpose of winding up." * 21 Aug 1929 - Liquidator duly appointed. * 18 May 1931 - Extraordinary Resolution - duly passed "Resolved that the books and documents of the Company and of the Liquidator thereof be retained by the said Liquidator, he undertaking to have then destroyed at the dissolution of the Company." * Finally wound up on 18 May 1931. |

|

|

|

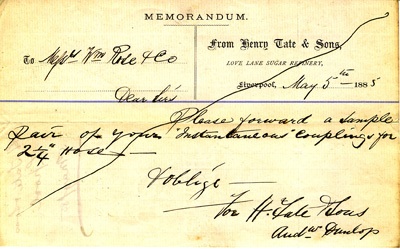

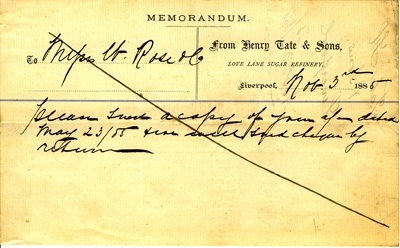

Two hand-written notes to William Rose & Co [Rose & Bray Fire Engineers, Deptford]. They are dated 1885 from Henry Tate & Sons, Love Lane Sugar Refinery, Liverpool. One asks for a sample of [fire hose] couplings, the other asks for a bill for work. My thanks to Barry Campbell, who writes ... "The firm of Rose Bray & Co were a firm of fire engineers. Makers of everything from engines, fire escapes to hoses. They were quite a large concern in the era the letters, invoices etc were sent and had some important customers. They invented and patented a new type of "instant fire hose coupling" about this time. Amongst their papers, I have had many requests for unpaid monies, which may help to explain their sudden and hard to find demise. It can also be the case that such a company gets 'absorbed' into another company, often a competitor. The last dates I have are pre 1900." Regarding Andrew Dunlop ... "The first chief engineer at [Love Lane] Liverpool was Andrew Dunlop, also a Scot and also possibly from Greenock, though this is not certain. We know little about him, but he was probably heavily committed in the building of the new refinery and certainly must have had a very difficult task in keeping a completely new and unknown plant operating successfully as well as coping with expansion, which was proceeding from the very earliest days." |

|

Liverpool's history is inextricably linked to the politics and power of a taken for granted everyday commodity. The white stuff in the packet, technically termed sucrose, is a simple dissacharide carbohydrate, containing a mix of fructose and glucose molecules and popularly known as sugar. Its main source before the nineteenth century, was a reed which Pliny the Elder claimed, "produced honey without the intervention of the bees"! Sugar cane, the quintessential slave crop, the "white gold" that assuaged Europe's seemingly insatiable cravings for sweet things, was arguably then and now, the major commercial source for the most political of all foodstuffs. "Strange that an article so sweet and necessary for human existence should have occasioned such crimes and bloodshed." That lucid indictment of sugar's nefarious history, by the Oxford scholar and former Prime Minister of Trinidad, Dr Eric Williams, evokes terrible images of transatlantic trade in human cargo, the African Diaspora and less obviously, the lubricating role played by eighteenth century Liverpool, which unequivocally developed as a "slave city first" ! Five hundred yards up from the Liverpool waterfront is the splendid town hall whose corridors are still adorned by busts of blackamoors and elephants. It was built in the late eighteenth century when powerful slave trade interests were coming up against popular agitation to end this evil trade, and in the decade when a drunken actor was cruelly booed by an audience of rich merchants inside Liverpool's Theatre Royal. George Cooke's response as he coruscated off stage, was scathing. "I have not come here to be insulted by a set of wretches, every brick of whose infernal town is cemented with an African's blood." Arguably in a city with one of the oldest indigenous black populations in Britain, it is not just thespian echoes that resonate in its outstanding civic buildings. Liverpool's infamous history as the capital of the slave trade has belatedly been addressed, but 65 years after Britain's part in that opprobrious trade ceased, the city took on another leading role. Love Lane refinery was established in 1872 as the mother plant and refining heart of Henry Tate's sugar dynasty. Tate & Lyle, the "Sugar Giant", has operations spread over five continents and over fifty countries but for ex-employees from Love Lane, historical consciousness is what counts today. 109 years after the ex-grocer set up shop in the Lane, an act of matricide was perpetrated. The tragically misnamed site, despite years of struggle to keep the plant open, was closed down in April 1981. Ostensibly this was because of the surplus capacity in cane sugar refining, caused by Britain's commitment to the Common Agricultural Policy of the European Economic Community, which heavily subsidised rival sugar beet production. The threat of closure indecently hung over the plant for ten years and a Liverpool Daily Post article in 1975 summed up what was at stake. "The loss of 2000 jobs near the city centre would be more than the end of a business enterprise - it would obliterate a community." Tragically the city which had been renowned internationally in the 1960s for the sound of the Mersey Beat and the Beatles was to become the first main victim of the sugar beet! "We have been living in an atmosphere of crisis for eight years, but when the blow comes it's like a sledgehammer in the solar plexus" declared John McLean on January 22nd 1981, in response to the issuing of the 90 day redundancy notices. McLean was secretary of the Workers Action Committee and known in the local press as "the scribe". That accolade was justified by his numerous letters and pamphlets and a moving valediction which concluded how "part of the structure of the city is being thrown to the wolves in the name of profit, in the name of the Common Market, and in the name of very greedy people". A solution to overcapacity in the port refining industries, and a definite lifeline for Liverpool, was cut off in 1980 when the Government rejected the EECs moderate proposals for reducing its structural sugar beet surplus. That would have meant reducing the British quota, which the Government, strongly influenced by the National Farmers Union, was loath to do. Margaret Thatcher, and Peter Walker the Minister of Agriculture, (now Lord Walker and non-executive Director of Tate & Lyle), emphasised that the closure of Love Lane was "entirely a commercial decision", which they would not interfere with. That said the chances of staving off closure in 90 days were remote to impossible. The valiant resistance by a genuine "Congress of Merseyside", that included workers, local MPs, councillors, and prominent church leaders, could not arrest the spate of rationalisations and redundancies which had tagged the region as "the Bermuda Triangle of British Capitalism". Generations of workers had refined raw sugar cane from predominantly African, Caribbean and Pacific countries but those historic links were terminally severed on April 22nd, when the Tate's workers joined one of the longest dole queues in Europe. "When the 'decline and fall' of Liverpool is eventually written, let it be said of the Tate & Lyle Action Committee that there was no disgrace in failure. Disgrace comes in not having tried. And by God they tried." That comment by Peter Leacey, one of the company's transport drivers, summed up a struggle that had actually lasted over 3000 days and culminated in "glorious defeat". In 1982 a year after closure, powerful thespian echoes resonated loudly, not just in Liverpool but throughout Britain. They articulated like a lorry into the national consciousness, not just of the best of British drama, but of the baneful effects of mass unemployment. The unemployment blackspot depicted in Alan Bleasdale's magisterially bleak, "Boys from the Blackstuff", was of course Liverpool, and his final scenes were filmed to the accompaniment of bulldozers flattening both the comically labelled Love Lane site and the Crystal Club which had been the social centre for Tate's workers. It was hard to conceive that the recruitment policy of this one time "family firm" had been that children followed parents into their employ, meaning that sometimes three generations would be working at the same time for Tate & Lyle. This seemingly permanent landmark that had dominated economically and physically the area just north of the City Centre exemplified how "all that's solid eventually melts into air". Indeed it was more than that. Community can be a warmly persuasive word and feeling, but not when it is blatantly blighted. TV screens now depicted that theatre of paternalism being physically deconstructed, as Bleasdale used the actual violence of Love Lane's demolition as stage prop for his fictional characters. Perhaps accidentally representations of "Tate & Lyle in the Community" were being tested for the first time by the most famous of Liverpool playwrights. The award winning series demonstrated more effectively than the unemployment demonstrations of the early 1980s, the sheer waste, futility and demoralisation of being without work in Thatcher's Britain. In the closing scene Chrissy, Logo and Yosser (Gis a job) Hughes, are seen leaving a manic "pub redundancy party" in the Green Man and tramping disconsolately alongside the refinery walls. Despite Bleasdale's impeccable craft skills, the irony was that the writer was only subliminally aware of the proxy voices of the boys and girls from the Whitestuff, when he wrote that last compelling piece of dialogue. "What's going wrong Logo?" asks the dejected Chrissy. "Everything La, everything." There were no smiles. This was the real Tate & Lyle, the soulless global corporation that Henry Tate, the entrepreneur and philanthropist had unintentionally bequeathed to the world.

...... Ron Noon, 10 January 2001.

|

|

Love Lane Lives ... For a number of years now, Ron Noon, Senior Lecturer in History at LJMU, has been trying to develop a project highlighting the struggles of the former employees of Tate & Lyle's Love Lane Refinery in Liverpool, both before and after its closure in 1981. With invaluable help from others, and Lottery funding, the project website went online 1 Dec 2008. Still an ongoing project, the website already includes a 46 minute film, background notes and Ron's blog. A facility will be developed to enable people to submit video histories to the project team. These will be edited and made available on site. Click to visit Love Lane Lives, the film, the history, the blog. |

|

|

|

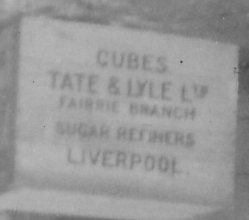

I bought this unused postcard because of the sugar connection. At worst it's a group of folk somewhere in the country who just happen to have a Liverpool sugar cubes box; at best it's a group of office workers from Fairrie's prior to its eventual closure. As well as the main refinery on Vauxhall Road, Fairrie's had smaller premises in the city at Raymond St, Hornby St, Victoria St, Black Diamond St, Green St, Portland St and Burlington St. The date must be later than 1929 when Fairrie's was consumed into the Tate & Lyle empire, and at the latest 1936 given the reverse of the postcard shows the "K Ltd" stamp box. The Vauxhall Rd refinery was closed in 1937. |

|

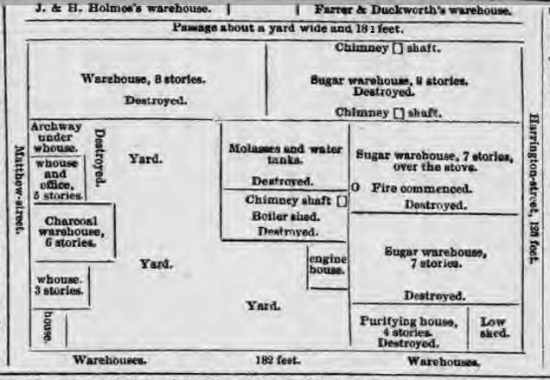

Fire broke out during the breakfast hour, early on 29 Dec. It's spread was rapid and some 120 men ran for their lives. Some were on the upper floors of the various buildings and leapt from windows to lower roofs, or down drainpipes (already hot from the fire), or down ladders that were soon put to the buildings. Some were seriously injured from falls and/or burns and transported the hospital. Just one worker died in the fire, and another died later in hospital; some were left disabled; all were out of work. A fund was set up to help them. |

|

|

... and but for the skills of the firemen and the employees of adjoining businesses it would have been much worse, for whilst the roofs and machinery crashed down through the floors they managed to stop the spread of the fire to neighbouring buildings. [The long newspaper report in the Liverpool Mercury for 30 Dec 1843 gave the above plan, the graphic details and the names of some of the workers whilst describing their escapes. The Mercury's reports over the following days/weeks, along with those of the Liverpool Mail and those further afield, continued to describe the effects of the fire and the plights of the men.] |

|

|

|