I left McGill for the University of Birmingham in February 1972 to take up a post as a meteorologist in the Department of Electronic & Electrical Engineering. This followed contact by telephone with Professor E.D.R. Shearman. He had newly overseen the development of a weather radar with an offset Cassegrain antenna and thus an unobstructed beam shown below. It operated with waves of quite short length, 5 cm, so the beam was nice and narrow. The radar was not yet operational so I had no meteorological data with which to work. Such C-band radars suffer severe attenuation from rain, and we hoped to study this. We were monitored by Britain's most celebrated radar meteorologist, Keith Browning who came from Imperial College, one of the world's best meteorology departments. He did not think a great deal of me, and there were endless delays.

I feel that there have been endless delays in our learning to comprehend the turbulent fractal character of cumulus clouds. In July 1959 one of the world's greatest hailstorms - the Wokingham storm - swept eastwards across southern England. It reached altitudes of 16 km, nearly twice that of more usual storms. It was observed by a radar newly put into service by Frank Ludlam with his student Browning at Imperial College and they became famous: Their easily comprehended model of steady airflow stopped people from thinking. Photographic studies of cumulus convection became few and far between for a long time.

Amer Al-Ubaidy was a Major in the Iraqi Air Force. As a Ph.D student he developed the software for the new radar. He was extremely bright and proud like an Arab stallion. I tried to help by tackling one of the problems, and I remember spending an entire weekend working on this, only to find that Amer had produced a better solution. I have casette tapes of Amer amiably explaining to me the intricacies of his software; also of talks with Keith Browning about our future activities. Keith would make points to which I had no sensible responses; no wonder he considered me effete. In the photo above Amer is seen holding forth to Acharyulu and Ahmet Fer. We were all in suits for an open day to show off the radar.

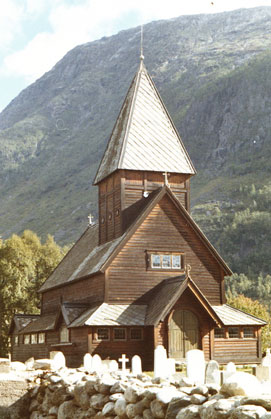

The young student Acharyulu and I drove my Austin 1100 car via Newcastle to Lillehamer in Norway for a Conference on Electromagnetic Wave Propagation. We slept under the eaves of Fantoft stave church near Bergen, enjoying camping out in rough clothes before getting smart for the Conference. On 14 Sep 72 I got a nice sunset stereo while lying on my back. We played many games of chess, with results marginally in favour of Achary. Described in the book by Roar Hauglid on "Norwegian Stave Churches", published in 1970 by Dreyers Forlag, Oslo, I photographed the largest extant stave church in Norway at Heddal (left) and an old one, Røldal (right):

Achary and I drove home via Denmark, Germany and Holland. Achary had never experienced a nightclub, and we found one in Hamburg. We found the girls fairly interesting, but were glad to escape back into the country. After we got home the car engine needed to be replaced.

Ahmet Fer had an English girkfriend of whom we were all very fond. They both came to visit my home in Haslemere. The time came for her to visit Ahmet's family in Turkey. She did not survive this ordeal and they broke up; she was heartbroken. I was glad that such stresses never affected me, and wonder how it is that romances can break down with never any possibility of recovery.

I got reviewing help from my McGill professor friend Roddy Rogers to produce a short paper on "Collision frequencies of raindrops" for the IEEE Trans. Antennas & Propagation (July 1977). I showed that collisions occurred sufficiently often that a variety of drop shapes needed to be considered. Roddy completely forgot this, and wrote another short paper on "Raindrop Collision Rates" in J. Atmos. Sci., (1 Aug 1989). He showed that collision rates were sufficiently infrequent to allow the formation of spectra of drop sizes which resemble those one might expect if conditions in a rain shaft are allowed to settle down towards an equilibrium. We assumed the same conditions of the rain and produced similar numbers. He involved radar reflectivity in his work, hugely complicated - and subsequently wrote approvingly of my effort. In October 1984 my friend Roddy wrote for the Institute of Hydrology the most glowing letter of recommendation for a job that anyone could wish for.

Raj Gunawardana (seen at right above in a recent photo) is a very bright engineer with many successful patents to his name. I worked with him on the new radar in his early years at Birmingham - long hours through the weekends. He was always very friendly to me, admiring my Public School demeanour. One day we were trying out some new software I had written to control the scanning of the radar, and it went into an uncontrolled rotation of the antenna and tore apart the control cabling, because a mechanical stop designed to prevent such a thing had failed to operate. In the customary amicable atmosphere in the Department blame was not visited upon anybody. A day came when we had the radar working and there was some precipitation around for us to record. We found an isolated radar echo over Spalding, Lincolnshire, 120 km ENE of the radar; we located someone there to phone, and learned that a thunderstorm had just ruined their flower festival, while elsewhere it was sunny. This was very gratifying, and Professor Shearman instantly made use of our map of the rain at a meeting. The radar was later used to study the impairment of radio communications by ground clutter.

After funding dried up for radar meteorology at Birmingham I returned for 19 months to the Stormy Weather Group at McGill University to pursue studies of Alberta hailstorms. After 7 years at the University of Virginia I finally returned to England in September 1984 to become a research assistant in satellite meteorology at the Hooke Institute for Atmospheric Research at Oxford University. I was more or less free to pursue what seemed to be useful under the loose direction of John Eyre affiliated with Met Office. We used to play squash, and afterwards race our bicycles back to the Clarendon Laboratory through the streets of Oxford. As at Birmingham, everybody around seemed to be vastly cleverer than me. Carefully prepared morning coffee on the roof of the Department was feature of life, and I enjoyed meeting people. Sir John Houghton occasionally appeared. He would make a witty remark which would instantly buoy up one's spirits.

The Advanced Microwave Sounding Unit was in preparation, and I worked on what the space-borne radiometers would be able to see. Several channels closely spaced at frequencies near 53 GHz (wavelength 57 mm, about the size of a thumb) are at the edge in frequency of a band of absorption and emission by oxygen in the atmosphere. AMSU and its successors have lots of channels - great spectral resolution - for receiving various amounts of radiation from rain and ice in the atmosphere, and excellent scientific progress has been made in mapping storms by satellite and measuring rainfall.

I got several good stereo-pair photos among the buildings of Oxford, including my best architecture stereo of the Radcliffe Observatory.

A group of about a dozen of us would go running a few miles on a Tuesday evening, and then retire to the pub. I would bring along raw brussels sprouts which some people liked. Roger Saunders and Phil Watts were always fast runners, Keith Shine more sedate. Howard Roscoe always celebrated his birthday with a triathlon of modest length based at his home with the sublime singer Anne Ryan of Moving Tone. At weekends I used to drive home to Haslemere and privately indulge my weakness for smoking.