After sailing across the Atlantic and through the Panama Canal to San Diego, I had $100 with which to buy a Greyhound Bus ticket to Montreal, where I had a girlfriend, and prospects of employment as a metallurgist. I met young Dan Barklind of San Jose, full of wit, enthusiasm and gentleness. Together we rode the bus to San Francisco. There in the early morning I hitched a delightful ride on a meat lorry doing a round of the city on deliveries. I rode another bus to Sacramento. Thence after stopovers to walk the Bright Angel Trail the one mile down into the Grand Canyon, and another to see snow clothing Niagara Falls in white, I arrived in Montreal on 25 Jan 66. Under the snow Montreal was cold and I did not like the prospects I found for working as a metallurgist. In lists of career choices, "Metallurgy" is followed by "Meteorology". Christiane Schweiger and her family suggested that I try the Meteorology Department at McGill University and I was instantly accepted for the Master's degree programme by Walter Hitschfeld, who liked a British Public School Cambridge graduate who had just sailed the Atlantic. This was a golden age for bright young scientists. "We can't pay you anything until next Monday. Will that be all right?" An instant scholarship was arranged for me and I became engrossed in the McGill Master's Degree programme. Next door to the Meteorology Department was a student hostel at 3609 Univerity Street. Thus I had a magnificent lucky break. Student seminars were a feature of our training; let not the writing on a graph be too small to read; present the material clearly. John Stewart Marshall, founder of the McGill Weather Radar Observatory at Dorval near Montreal, tended to ignite with ire: "What have you plotted against What?" he would shout if the axes of a graph were not labelled clearly. Clever but sensitive souls used to be reduced to tears by these angry outbursts. One of his graduate students suffered a nervous breakdown. He and our other professors always cared greatly for their students and we enjoyed the best of graduate education. I was set to work measuring snowfall by attenuation of the beam of light from a transmissometer. One day I was deeply engrossed in this when a Cambridge MA in Metallurgy arrived in the post.

We had an excellent Meteorology M.Sc class; I was great friends with Tommy Warn; we would argue ferociously the relative merits of experiment and theory, while consuming smoked meat at Ben's. At first for relaxation I went skiing, north to the Eastern Townships (Quebec). I became acquainted with Roland and Margaret Byron-Scott.

McGill Outdoors Club (MOC) was wonderful. Members used to take off in a car to go skiing, camping and hiking, either to the north, or to the south of Montreal in the Adirondacks (NY), the White Mountains (New Hampshire), Jay Peak (Vermont) or Mount Katahdin (Maine), where on 20 July 69 I alone among our party of MOC members listened to the radio as Neil Armstrong became the first man to step on to the Moon. On my first visit to Alberta in 1967 I bought my own car, a North American Rambler called GT.

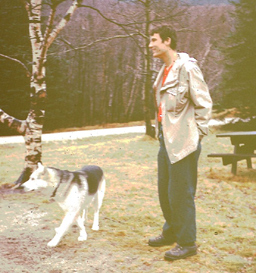

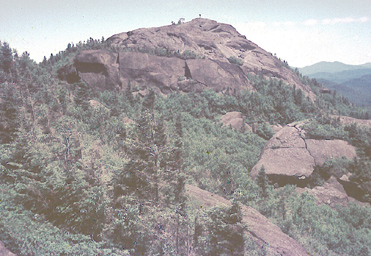

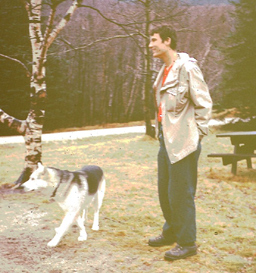

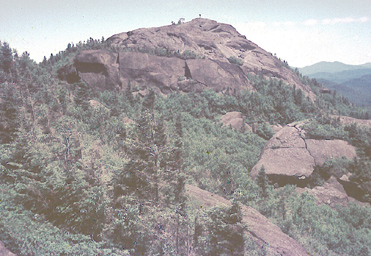

Arvo Koppel, Latvian Canadian, was a leading figure in MOC, tall, strong and gentle. Nowadays when I exclaim "Oh God!" I might be referring to Arvo. Below he is shown in late 1969 with his dog Henry. At left appear "new girlfriend" Andy McClintock according to a casette tape recording I sent home to my family in England; I was going to "take her to the pictures". She was with me and the mild-mannered, soft but not soft, Heather Munro. We were sitting by Saranac Lakes (NY). On that weekend of 5-6 July 1969 we canoed. Winds blew up. I paddled my canoe with two companions to shelter. Someone from another club like ours died after a capsize. At right is shown Mount Ampersand (1012 m) in the Adirondacks, NY, another place within easy reach of Montreal. [It has(?) a structure on its top.]

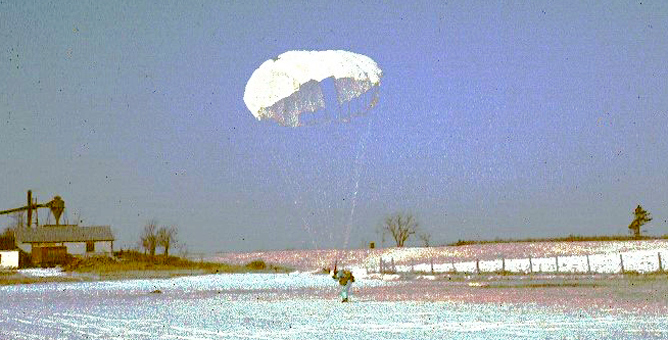

Under Bert St Louis of Les Hommes Volants students trained to parachute. I didn't like his nasal Quebecois French, but he worked us well. Ten hours of training cost $10, jumping off a plank at chest height. On 12 Nov 66 eighty McGill students jumped from about 3000' into a Force 4, latterly with ice pellets. Three students at a time flew with pilot and dispatcher. With a name beginning with "W" I had most of the day to watch others' reactions. A few whooped; most just grinned as eventually I did. Some expressed chagrin at being snarled in herbage or landing on a railway line; nobody was hurt.

I jumped again twice. Others reported hugely enhanced confidence after surviving parachute malfunctions. Getting more scared each time, I quit, like all but about 3 of our 80.

While I took a train trip to Vancouver to visit friends, a substantial snowfall in Montreal gave me enough material to write my first paper, for the Journal of Applied Meteorology. On this trip I met Rama Ramalingam, McGill student of industrial engineering, and together we toured Montreal's great Expo 67. Later when he became very prosperous in California he sponsored with a massive £500, half of my total, an abseil I enjoyed for Phyllis Tuckwell Hospice, British cancer charity. At this time the optics of my transmissometer were flawed, so the results from it were quantitatively unreliable, but this was not comprehended at the time.

The Alberta Hail Studies project was supplied with McGill students of the Stormy Weather Group led by J.S.Marshall, Walter Hitschfeld, R.H.Douglas and my M.Sc. supervisor K.L.S.Gunn, later joined by R.R.Rogers. After completing my M.Sc I took a job for a year as a Research Assistant taking stereo-pair time-lapse movies of young storms growing over the shallow eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains west of Red Deer, Alberta. I had two time-lapse movie cameras separated by a few kilometres which were aimed at the same storm. We got delightful movies of young storms from the hanger roof at the airport at Penhold, Alberta - sublimely peaceful and informative. I gathered many data and was then allowed to use them for another three years to produce a Ph.D thesis on visual and radar aspects of large convective storms. During my final year I was helped by a mild-mannered and conscientious student, John Kirby.

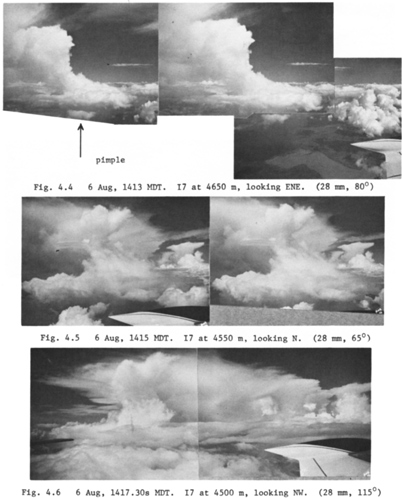

The Stormy Weather Group at McGill in the late 1960's had many distinguished alumni. The gentle Marianne English computed hail growth trajectories. John Marwitz, a big no-nonsense character, worked with Augie Auer, amiable and open, who always used to call me "Charlie Chick". They used aircraft from the University of Wyoming to seed clouds from the air. We burned flares which produced a smoke of silver iodide, which has a crystal structure like ice. The idea was to obtain large numbers of small ice pellets as opposed to smaller numbers of bigger hailstones. We tried burning flares under the "plateau", low flat cloud base free of precipitation and veils of virga, denoting the main updraught and easily recognizable in the photo shown below next to the main shafts of precipitation downdraughts. This seemed inconclusive; we also tried flying at middle levels close over the rising towers on the flank of a storm, and dropping flares into them as we passed.

I used to work all day every day, and felt that there was no way that any Professor could possibly know more than I did of the current science; I simply out-worked everybody else. There was no point in attending Conferences, because nobody would know more than me about my current interest. They were not always so smart, either. I was not happy to be awarded 100% in a Cloud Physics exam by my friend Professor Roddy R. Rogers; this implied that I knew everything about cloud physics. A good cloud calculation carries a large number of different categories of hydrometeor, from tiny no-see-em drizzle droplets to massive stones of ice.

Seen in the photo above taken on 4 July 68 is my first girlfriend, Angela Acland. On her right was my car GT; on her left was a Hillman Minx like the car we had in England. A friend of Peter Wingfield-Stratford, I met her in Lansdowne Road. Her father used to refer to her as "prime English beef". I found her extremely attractive; I was very physically aggressive. I drove her all over western Canada. Finally I took her home to Vancouver. Having just arrived, abruptly I felt unwelcome at her flat and took to my car in the middle of the night to get back to work. Unhappy, are we? Then let's just work on some cloud photo time-lapse movies. Among my elaborate case studies (See it clearly once and be for ever happy) was the evolution over ten minutes of cumulus towers of the Stettler storm of 1968. Big Wal paid a rare visit to my office to see how his Ph.D student was getting on. "This is fine, Charles", he said. "How many storms have you treated this way?" I was exhausted after three months of earnest toil and didn't have the answer he sought. He refused to read my lengthy compilations of evidence. Just KISS: Keep It Short and Simple. Walter Hitschfeld was always kind and friendly, and I enjoyed visiting him at home. I was his protégé, and later he expected me to remain in North America.

I have beautifully written letters from Cindy Phipps, black girl who was associated with Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario. We were very fond of one another and of the cartoon character Peanuts. To her I was always "Charlie Brown".

Alastair Fraser was at Imperial College in London with R.S.Scorer, who wrote the classic book "Clouds of the World". This included stereo-pair photographs, of which Alastair was a proponent. He demanded that I put on for him a display of stereo-pair time-lapse movies at my office at McGill. He was duly impressed - so I also had to learn to see stereo-pairs without using a stereoscope. This took me a week, and persuading a majority of the world's population to see them has become my main mission in life, hitherto stunningly unsuccessful. I can see them easily! I work for the creation, not necessarily by me, of a best-seller:- "About Nine Tries at Stereo-Pairs:- Heaven". Plenty of good material may be found within.

I became great friends with one of our research professors of Climatology, Eberhart Vowinckel. Over relaxed weekends I joined his family at their retreat on an island in the St Lawrence River, driven there by law student Thomas Vowinckel. At work, we all had to learn mainframe computing using decks of cards written in Fortran and run overnight by friendly operators. Dr Vowinckel used to complain that since the advent of computers his scientific output had halved.

I have an observant letter from The Department of Meteorology, Damascus, from the quiet and delightful Ali Maatouk dated July 1968. He stayed 5 nights at my old flat at 28 Lansdowne Road; he liked London better than Paris or Rome, where he also took his new McGill M.Sc.

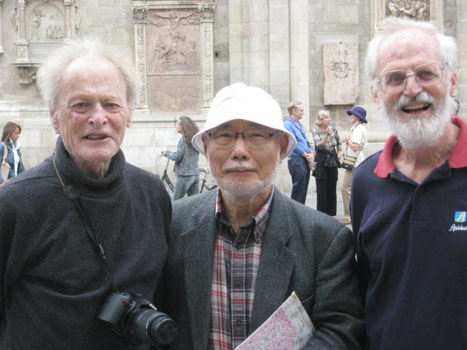

The Austrian Dr Gerd Ragette is seen at right above receiving instruction from our glaciology friend Atsumu Ohmura, as always in demand as an author and speaker. Gerd later wrote me thoughtful letters on paper of the Zentralanstalt für Meteorologie und Geodynamic. We have climbed together Aonach air Chrith in Scotland, around the Drei Zinnen in Italy and among mountains south of Vienna. He contends that ~ 95% of what goes on inside the brain of a human is rubbish. One only has to compare one's mental ferment with the exterior a few centimetres away to perceive what he means. However, Man has been to the Moon.

Atsumu, not I, married Andrée McClintock. I too could probably have made a successful marriage with her, although she did become involved in Financial Services. Atsumu joined the great glaciologist Fritz Müller at ETH in Zurich. In December 1970 he suddenly found after some skating that he had dead muscles in both lower legs, erroneously diagnosed as "diomatmiositis", of which there were only ~4 known cases. A muscle transplant operation might be fatal. A large group of expert doctors came to assess the case and decide whether Atsumu should risk death by slow progress of the disease up to the heart, or face a muscle transplant operation with rather similar risks. They could not reach a consensus. Atsumu pointed out that it was his body and he would like to risk the muscle transplant. The doctors took a final look at the dead muscles: Lo! they were not dead: they were recovering ... slowly! In May Andrée arrived to help to heal Atsumu. They had a brief passionate quarrel when Andrée lost her temper with some bureaucracy. She tells about her rural father from County Donegal in Ireland, who flew during WWII and then joined the Royal Canadian Air Force, and her aristocratic French Canadian mother. They remained firmly married for many decades while never agreeing about anything. Andrée received intimidating strictures from her mother on responsibility and commitment to a man, but knew what she wanted. During the summer she and Atsumu became engaged, and now they have three children, a brilliant happy ending.

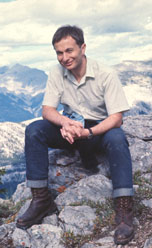

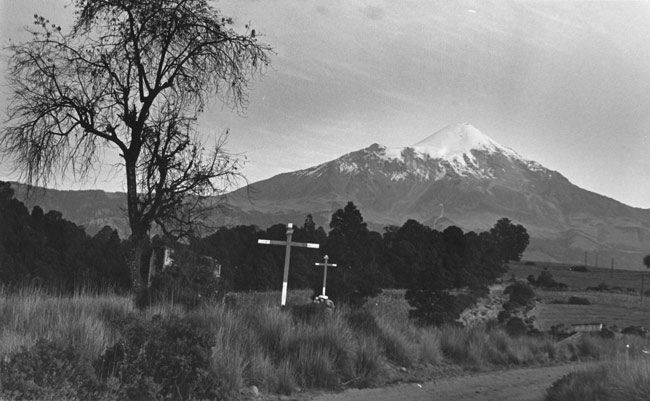

Our greatest MOC trip was to Mexico to climb Orizaba, Citlalteptl, the country's highest mountain at 5636 m. In December 1969 we drove down from Montreal in 50 hours, rotating our seating in the car every 5 hours. Once in Mexico we stopped the car every time any one of us wanted to take a picture. Arvo Koppel, student of engineering, had climbed Mount McKinley; he trained and led us. His dog Henry had to be left behind. Janis Kraulis, Latvian student of English, said the least - sometimes caustic. He climbed with Arvo, and they were strong. Pursued by a truck, Janis drove down a steepening hill into the little town Tamazunchale rather fast, adhering strictly to the correct side of the road, with unflinching concentration. Pictures he took had a gentle quality. There didn't seem to be anything special about his methods. Rob Curtis had our Spanish, a thermometer and useful U.S. navigation data. On the tapes I made of our chatting, he and I talked the most, but nobody dominated. My elite companions were of age ~21; I was 31: I felt like ~20½. Arvo's overall leadership was the greatest. We all had to agree with him that we would use sleeping bags everywhere and spend the minimum. We enjoyed ourselves.

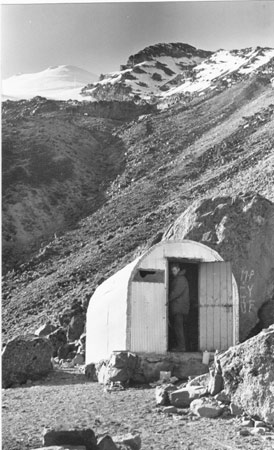

We climbed the Pyramid of the Moon at Teotihuacan, alone on the site except for a security guard who had quite cordially opened the car for us when we got down. We met lots of children when we stopped for petrol, who would work as a team, one distracting us while another attempted to lift belongings unless carefully watched. I have a casette tape of our trawling for map information on Orizaba while attanding a watering place frequented by sugar cane farmers and their burros. Rob's question in Spanish would be followed by a farmer's gruff answer, and then Arvo's mumbled reaction. Arvo and I enjoyed a tranquil night in sleeping bags the night before starting our ascent by jeep. We climbed to the refuge shown below for a night of acclimatisation where I am seen (right) standing outside the hut at 4260 m. Other climbers came by and went on upwards without waiting around to acclimatize. Most of these failed. Arvo led us up to ~4600 m further to acclimatize in our tents over another night. This worked well except for Rob, who retired next morning after headaches and nausea. Some of our best pictures - mostly by Janis - are shown below:

After the climb we drove to Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where Janis and I slept at peace on the beach. Late in the night we received a lot of wind-blown sand from a Tehuantepecer. We drove to Salina Cruz, which I had visited while on passage aboard the "Ondine" shortly after encountering another of these wind storms four years earlier. On the Pacific coast Arvo and Janis watched a turtle slowly climbing up the beach, and early on ~30 December swam in peace in the nude. We drove to Oaxaca, good for protracted bargain buying of blankets and ponchos. After many hours of application, Arvo achieved a significant price reduction when his first seller was bumped by a second seller and panicked. Nearby the hill-top ruins of the ancient city of Monte Alban were neat and impressive. We liked Acapulco, white skyscrapers built neatly around the golden arc of the bay which it encloses. In Taxco, tourist down for articles of silver, Janis and I played a lengthy game, full of careless mistakes, with some huge chess men, while the others browsed along the boring row of main street shops. Mexicans everywhere were cordial in their advice and tolerance; when we arrived disshevelled at a cafe, nobody minded our habit of going off in series to monopolize the washroom. We had to get home, so not long was spent at the wonderful Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. The country is an array of individual, separate, places. The Museum attempts to treat developments through time as well as space - fascinating. On the way home, now in continuous four-hour shifts, We stopped by the Curtis home in Westport, Connecticut, and were given a glorious dinner and presents. After struggling home to snowy Montreal, battered and drinking oil, my faithful car GT was finally laid to rest.

I inherited from Gerd Ragette a Pontiac I called the Queen Mary. It traversed the continent several times. Early one morning in the middle west I was stopped by a nasty Police Officer who had bombed up behind me. Curious about my Quebec licence plate, he pulled me over and upbraided me for exceeding the speed limit. With my impeccable British civility I explained that the Queen Mary was never driven faster than 50 mph; he reluctantly let me go. The car was superb. I slept alone in it after my Ph.D for 2 weeks. Westbound in 1971 in Calgary the generator died, so I parked the car down a slight incline and laid out my sleeping bag in a dry ditch for the night. I was woken by a bright flashlight. "Ah! You're alive, sir! I'm very glad because we had a report of a body in the ditch. Would you mind getting a bit closer to your car and then you won't look quite so dead." With the generator effortlessly sorted in the morning, I picked up younger son Charles of Walter Hitschfeld, who was working on accounts at Waterton Lakes National Park, Alberta. My photo below shows him in the bison enclosure on 27 July 71. Gone were the days of 60 million bison. I carried on to rendezvous with Dave Nunn of Imperial College to climb Mount Rainier, Washington. He never made it; he doubted that I would; he lost all his kit and was seduced by a girl and I never heard from him. I reconnoitred in short trousers and got sunburn. I was in bed in Paradise Inn for five lonely days. I got the altocumulus lenticularis photo on 6 Aug 71, vastly cheered by Mark Hisle (10), son of a mountain shopkeeper, who as shown at right always seemed to walk on air.

Latterly as part of the Alberta Hail Project I photographed storms while flying with Intera Environmental Consultants.

In 1975-7 as a research associate I joined in this activity with Rob Inkster and his team of 16 cheery pilots of Intera Environmental Consultants. I worked as observer, sitting in the back of a little Cessna or Piper Aztec working my camera and notebook. Sometimes we flew above 3500 m and would need oxygen; I would be told to suck on a tube periodically which was passed around. Flares were dropped from a rack in the back of the plane next to my seat. I lost an unimportant camera case through this bomb bay. The photo on top below shows an innocuous storm of 3 Aug 76, seen at 1531 MDT from ~1700 m looking west with Jim Runyon and Glen Davis. Below at left is seen the view at 1450 MDT on 26 July 76 flying at ~200 m above Highway 11 just west of Rocky Mountain House to act as a communication relay station. There was light turbulence. At centre are shown girls at the centre of activity on 12 Aug 76. On 4 July, flying in formation with Al Wilson and Pat MacDougall the bare behind of Jim Runyon was presented for my camera: seen at right, the shot was not very good.

In 1967, hesitant about going for the Ph.D degree at McGill, I was given Career Advice by the UK Trade Commissioner Sir Peter Tennant in Montreal. We had both been put up to this meeting by my mother, and considered it a waste of time. "Well Charles," said Sir Peter, "why don't you just - go as far as you can see - and then - see how far you can go!". Brilliant!